Chemically, DNA is a long polymer of simple units called nucleotides, with a backbone made of sugars and phosphate groups joined by ester bonds. Attached to each sugar is one of four types of molecules called bases. It is the sequence of these four bases along the backbone that encodes information. This information is read using the genetic code, which specifies the sequence of the amino acids within proteins. The code is read by copying stretches of DNA into the related nucleic acid RNA, in a process called transcription. Most of these RNA molecules are used to synthesize proteins, but others are used directly in structures such as ribosomes and spliceosomes.

Within cells, DNA is organized into structures called chromosomes and the set of chromosomes within a cell make up a genome. These chromosomes are duplicated before cells divide, in a process called DNA replication. Eukaryotic organisms such as animals, plants, and fungi store their DNA inside the cell nucleus, while in prokaryotes such as bacteria it is found in the cell's cytoplasm. Within the chromosomes, chromatin proteins such as histones compact and organize DNA, which helps control its interactions with other proteins and thereby control which genes are transcribed.

DNA is a long polymer made from repeating units called nucleotides. The DNA chain is 22 to 26 Ångströms wide (2.2 to 2.6 nanometres), and one nucleotide unit is 3.3 Ångstroms (0.33 nanometres) long.[3] Although each individual repeating unit is very small, DNA polymers can be enormous molecules containing millions of nucleotides. For instance, the largest human chromosome, chromosome number 1, is 220 million base pairs long.

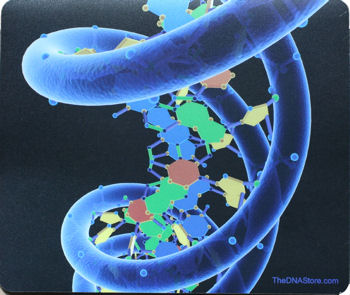

In living organisms, DNA does not usually exist as a single molecule, but instead as a tightly-associated pair of molecules.[5][6] These two long strands entwine like vines, in the shape of a double helix. The nucleotide repeats contain both the segment of the backbone of the molecule, which holds the chain together, and a base, which interacts with the other DNA strand in the helix. In general, a base linked to a sugar is called a nucleoside and a base linked to a sugar and one or more phosphate groups is called a nucleotide. If multiple nucleotides are linked together, as in DNA, this polymer is referred to as a polynucleotide.

The backbone of the DNA strand is made from alternating phosphate and sugar residues. The sugar in DNA is 2-deoxyribose, which is a pentose (five carbon) sugar. The sugars are joined together by phosphate groups that form phosphodiester bonds between the third and fifth carbon atoms of adjacent sugar rings. These asymmetric bonds mean a strand of DNA has a direction. In a double helix the direction of the nucleotides in one strand is opposite to their direction in the other strand. This arrangement of DNA strands is called antiparallel. The asymmetric ends of DNA strands are referred to as the 5′ (five prime) and 3′ (three prime) ends. One of the major differences between DNA and RNA is the sugar, with 2-deoxyribose being replaced by the alternative pentose sugar ribose in RNA.

The DNA double helix is stabilized by hydrogen bonds between the bases attached to the two strands. The four bases found in DNA are adenine (abbreviated A), cytosine (C), guanine (G) and thymine (T). These four bases are shown below and are attached to the sugar/phosphate to form the complete nucleotide, as shown for adenosine monophosphate.

These bases are classified into two types; adenine and guanine are fused five- and six-membered heterocyclic compounds called purines, while cytosine and thymine are six-membered rings called pyrimidines.[6] A fifth pyrimidine base, called uracil (U), usually takes the place of thymine in RNA and differs from thymine by lacking a methyl group on its ring. Uracil is not usually found in DNA, occurring only as a breakdown product of cytosine, but a very rare exception to this rule is a bacterial virus called PBS1 that contains uracil in its DNA.[9] In contrast, following synthesis of certain RNA molecules, a significant number of the uracils are converted to thymines by the enzymatic addition of the missing methyl group. This occurs mostly on structural and enzymatic RNAs like transfer RNAs and ribosomal RNA.

Each type of base on one strand forms a bond with just one type of base on the other strand. This is called complementary base pairing. Here, purines form hydrogen bonds to pyrimidines, with A bonding only to T, and C bonding only to G. This arrangement of two nucleotides binding together across the double helix is called a base pair. In a double helix, the two strands are also held together via forces generated by the hydrophobic effect and pi stacking, which are not influenced by the sequence of the DNA. As hydrogen bonds are not covalent, they can be broken and rejoined relatively easily. The two strands of DNA in a double helix can therefore be pulled apart like a zipper, either by a mechanical force or high temperature.[15] As a result of this complementarity, all the information in the double-stranded sequence of a DNA helix is duplicated on each strand, which is vital in DNA replication. Indeed, this reversible and specific interaction between complementary base pairs is critical for all the functions of DNA in living organisms.

The two types of base pairs form different numbers of hydrogen bonds, AT forming two hydrogen bonds, and GC forming three hydrogen bonds (see figures, left). The GC base pair is therefore stronger than the AT base pair. As a result, it is both the percentage of GC base pairs and the overall length of a DNA double helix that determine the strength of the association between the two strands of DNA. Long DNA helices with a high GC content have stronger-interacting strands, while short helices with high AT content have weaker-interacting strands.[16] Parts of the DNA double helix that need to separate easily, such as the TATAAT Pribnow box in bacterial promoters, tend to have sequences with a high AT content, making the strands easier to pull apart.[17] In the laboratory, the strength of this interaction can be measured by finding the temperature required to break the hydrogen bonds, their melting temperature (also called Tm value). When all the base pairs in a DNA double helix melt, the strands separate and exist in solution as two entirely independent molecules. These single-stranded DNA molecules have no single common shape, but some conformations are more stable than others

DNA damage

DNA can be damaged by many different sorts of mutagens. These include oxidizing agents, alkylating agents and also high-energy electromagnetic radiation such as ultraviolet light and x-rays. The type of DNA damage produced depends on the type of mutagen. For example, UV light mostly damages DNA by producing thymine dimers, which are cross-links between adjacent pyrimidine bases in a DNA strand. On the other hand, oxidants such as free radicals or hydrogen peroxide produce multiple forms of damage, including base modifications, particularly of guanosine, as well as double-strand breaks. It has been estimated that in each human cell, about 500 bases suffer oxidative damage per day. Of these oxidative lesions, the most dangerous are double-strand breaks, as these lesions are difficult to repair and can produce point mutations, insertions and deletions from the DNA sequence, as well as chromosomal translocations.

Many mutagens intercalate into the space between two adjacent base pairs. Intercalators are mostly aromatic and planar molecules, and include ethidium, daunomycin, doxorubicin and thalidomide. In order for an intercalator to fit between base pairs, the bases must separate, distorting the DNA strands by unwinding of the double helix. These structural changes inhibit both transcription and DNA replication, causing toxicity and mutations. As a result, DNA intercalators are often carcinogens, with benzopyrene diol epoxide, acridines, aflatoxin and ethidium bromide being well-known examples.Nevertheless, due to their properties of inhibiting DNA transcription and replication, they are also used in chemotherapy to inhibit rapidly-growing cancer cells

In 1943, Oswald Theodore Avery discovered that traits of the "smooth" form of the Pneumococcus could be transferred to the "rough" form of the same bacteria by mixing killed "smooth" bacteria with the live "rough" form. Avery, along with coworkers Colin MacLeod and Maclyn McCarty, identified DNA as this transforming principle. DNA's role in heredity was confirmed in 1953, when Alfred Hershey and Martha Chase in the Hershey-Chase experiment showed that DNA is the genetic material of the T2 phage.

In 1953, based on X-ray diffraction images taken by Rosalind Franklin and the information that the bases were paired, James D. Watson and Francis Crick suggested what is now accepted as the first accurate model of DNA structure in the journal Nature.Experimental evidence for Watson and Crick's model were published in a series of five articles in the same issue of Nature. Of these, Franklin and Raymond Gosling's paper was the first publication of X-ray diffraction data that supported the Watson and Crick model, this issue also contained an article on DNA structure by Maurice Wilkins and his colleagues. In 1962, after Franklin's death, Watson, Crick, and Wilkins jointly received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. However, speculation continues on who should have received credit for the discovery, as it was based on Franklin's data.

In an influential presentation in 1957, Crick laid out the "Central Dogma" of molecular biology, which foretold the relationship between DNA, RNA, and proteins, and articulated the "adaptor hypothesis". Final confirmation of the replication mechanism that was implied by the double-helical structure followed in 1958 through the Meselson-Stahl experiment. Further work by Crick and coworkers showed that the genetic code was based on non-overlapping triplets of bases, called codons, allowing Har Gobind Khorana, Robert W. Holley and Marshall Warren Nirenberg to decipher the genetic code. These findings represent the birth of molecular biology.

SIR FRANCIS CRICK(RIGHT) WITH JAMES WATSON (LEFT.)

Pioneer James Watson in 1957 with a molecular model of DNA.

SOURCE: WIKIPEDIA

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home